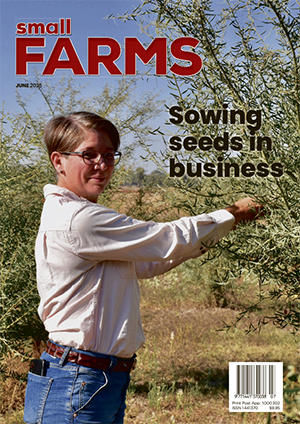

While woodlots are a long-term proposition, there are a host of benefits along the way: as well as being another way to add cashflow to the farm, commercial tree crops can complement farming activities and protect livestock, land, water and wildlife.

For landowners thinking of planting woodlots, the old adage holds true: there are only two right times to plant trees: one was 20 years ago, the other is right now.

According to Australian Forest Growers executive officer Sarah Paradice, Australia is well-placed to grow plantation timber that can meet the export and domestic demand for house framing, appearance-grade products (shelving, trim, cupboards, furniture and floorboards), plywood, posts, poles and paper products.

“You don’t have to wait 40 years for a return from farm forestry,” she explains “the sort of economic returns you make, and how quickly, depends to a large degree on your expectations and the type of farm forestry you undertake.

“Your own goals will determine whether you grow trees for short, medium or long-term returns. Whether you put in a small woodlot of mixed indigenous species, or a large plantation of single, fast growing highly commercial species, or a wide-spaced agroforest, or some other configuration, will be affected by such factors as:

- personal and family circumstances – age, health, family life cycle;

- the type of farm enterprise you have now, and its financial position – debt load, cash flows, overheads, disposable income, tax position, the need for quick returns;

- amount of land available, and its quality and suitability;

- availability of other resources – water, labour, equipment, skills, time, finance;

- individual and family values and aspirations;

- the need to make trade-offs between commercial returns, and land care and conservation benefits.

“These factors will all have a bearing on the likely success of whatever farm forest you grow,’’ Sarah says.

One family which has seen the rewards and returns from woodlots are the Brookmans, owners of The Food Forest; a 20ha permaculture farm and learning centre at Gawler, just north of Adelaide, where they produce more than 160 varieties of organically-certified fruit and nuts, wheat and vegetables, free-range eggs, honey, carob beans, Australian native foods, nursery plants and timber.

Annemarie and Graham Brookman, along with their children Tom and Nikki, have run the land since 1983 and during the last 30 years, have planted a variety of timber which benefits land, beast and bank balance.

“We have about a hectare of forest, a couple of kilometres of multi-row windbreaks and half a kilometre of river corridor,” says Graham.

While not situated in traditionally high rainfall country, the deep river clay-silt soil has proven capable of timber production and indeed benefited from its plantings. Species grown include Casuarina cunninghamian and Obesa, Callitris preisii, a range of eucalypts and long-lived acacias.

“Over the last five years, we have received around 350-500mm annual rainfall, mainly toward the lower end. There is undoubtedly some shallow groundwater influence from the nearby river and large red gums thrive on its channel banks,” says Graham.

Among the forestry plantings is the 0.03ha Hardwood Forest of Eucalyptus camaldulensis variety Albacutya (selected for salt tolerance), which is used to produce poles for horticulture structures such as hoop-houses and other light buildings like bird hides. It yields firewood at a rate equivalent to 20 tonnes per hectare, per year. “Potentially quite profitable at a retail value about $300 per tonne, even allowing for 15 per cent loss of weight in curing, plus felling, transport and marketing,” says Graham.

“Coppicing occurs on a seven-year rotation, and we settled on 5m x 3m spacing after a trial showed that we couldn’t sustain the 1000 stems per/ha used in Adelaide Hills plantings at the time.”

The Brookmans also have a 0.24ha softwood forest: comprising a 5m x 3m main framework of Pinus canariensis, one of the most drought tolerant of the pines, which is expected to produce 6m sawlogs at the age of about 40 years. The premium, fine-grained reddish wood is suitable for furniture production.

“Much of the forest has been interplanted with oaks Quercus macrocarpa and Quercus canariensis, bringing the density up to about 750 stems per hectare. The concept is that the pines will be felled into the 5m inter-row spaces and leave an oak forest as a permanent agroforestry enterprise with livestock eating the acorns in autumn,” says Graham.

The 0.5ha agroforestry paddock is used for cropping and haymaking as well as growing two rows of Gleditsia tricanthos for shade and shelter for livestock (sheep and geese). “The honey locusts drop their energy and protein-rich pods in autumn, and being deciduous, they do not significantly compete with the crops or pastures,” explains Graham.

The family also maintains the windbreaks for shelter and biodiversity. “Our bird list boasts about 90 species,” says Graham. “We also harvest firewood for our heating purposes and to trade with friends and acquaintances.

“Two of the windbreaks wrap around and become part of the 1.3ha biodiversity block, which contains 140 species of native Australian plants including locally indigenous trees, shrubs, grasses and groundcovers.”

The so-named Floodable Forest becomes inundated every few years and comprises species that love a good flood event and can tough-out total immersion for weeks, as well as handling Phytophthora which is endemic in the catchment of the Gawler River.

The species are mostly Acacia salicina, Casuarina cunninghamiana and Acacia stenophylla.

“The acacias are capable of suckering if smashed by a passing log and provide great riverbank stability. We will harvest these species for furniture timber at perhaps 40 years of age; meanwhile they are great for biodiversity and are not particularly flammable in the case of bushfire,” says Graham.

Having enjoyed and at times, endured, farm forestry for more than 30 years, Graham believes species selection, good preparation and layout, combined with early care – particularly weed control, is a worthy investment. Thinning and coppicing is also part of the job, he adds.

When starting out, the Brookmans sought industry leaders and best-practice research before embarking on the forestry side of their permaculture farm.

“Forestry and agroforestry are strongly endorsed in permaculture design so we initially relied upon permaculture texts for species choice. From there, we devised a two-day farm forestry course (taught at our farm) with foresters employed by Primary Industries in the ’80s, and when Roseworthy Ag College introduced agroforestry as a subject, we interacted a lot with Dr Ian Nuberg in terms of tree care and farm design. These people, along with Rowan Reid at Melbourne Uni, wrote a number of texts which are still the best information on sustainable agroforestry today,” says Graham.

“We also attended grower field days and an inspirational farm forestry trip to Kangaroo Island with the community group Australian Forest Growers.”

As the farm developed and grew, forestry became integral to the big picture, with forestry plantings incorporated into the whole farm plan in terms of flooding, fire, shade, shelter, fuel, building materials, fodder, privacy, noise amelioration, biodiversity and erosion control.

But Graham believes these are just a few of the good reasons for looking carefully at what farm forestry can offer.

“You may wish to make more money or to set yourself up with a nest egg for your retirement, or to offset tax. You may have a commitment to the environment or care about the health of the planet we hand on to our children. Perhaps you like the idea of planting and caring for trees from which fine timber products will be made.

“Farm forestry does not necessarily mean hectare upon hectare of pine trees, it can mean well managed windbreaks, woodlots, or timber belts of native species too.”

And for well-planned and managed woodlots, there’s reward for effort, explains Graham.

“In the Adelaide Hills it is quite reasonable to expect returns equating to $1000 per hectare of forest per year.

“Different wood products offer vastly different levels of income, and demand varying amounts of skill and effort. Firewood may be worth $20 per tonne in the standing tree or $100 sawn on farm and a yield of over 10 tonnes per year should be achievable per hectare, providing a total profit of up to $1400 per hectare in the 10-year span to first harvest. However, if the landowner sawed the timber with un-costed labour, the profit may be more like $3500 per hectare.

“Sawlogs (for timber) are measured by volume rather than by weight and can command over $80 per cubic metre. For the 550 cubic metres of Pinus radiata wood which may be produced off a hectare in 25 years, an income of $44000 is possible.

Eucalyptus maculata (Spotted Gum) is one of the straightest and tallest growing species available for the Adelaide Hills and produces “appearance grade” timber for furniture, panelling and other purposes as well as for structural applications.

“Well-sawn and cured Clearwood could be bringing in prices equivalent to $500-$1000 in real terms per cubic metre in 25 years. At 200-400 cubic metres per hectare the devotion of part of your property to eucalypt forestry doesn’t sound such a bad idea,” says Graham.

“Even trees on the stump are estimated to bring up to $100 per cubic metre. If you foresee a need to sell your land before the maturity of the trees, the value of the forest is now routinely factored into the value of the land so you don’t necessarily have to wait 25 years to benefit from planting your gums. Why wait?”

Like food production, much of the income involved in forestry is at the value-adding and sales stage of timber and firewood.

Graham advises newcomers to woodlot development to carefully analyse the property in terms of stock movement, grazing and protection. Pick out the most valuable land for particular production purposes. Think about access and vehicle movement. Integrate plantings with a comprehensive fire plan and know the markets for the species planted.

Furthermore, consider proximity to port loading and milling facilities if venturing down the plantation timber path. A distance of greater than 50km from the nearest port or mill is likely too far to justify some plantations.

“Your geographic location may also limit your options, in that too great a distance from a preserving plant may take out poles as a potential product, whilst distance from a city may eliminate firewood,” says Graham.

“The size of your plantings can also be critical. A firewood lot yielding less than 100 tonnes is unlikely to be of interest to a firewood contractor. Talk to potential buyers before planting. In some cases, contracts can be signed with buyers and sometimes they provide an advisory service to growers.

“The issue of carbon farming is still on the table. In the absence of a national policy, most Australian plantings have been done in the international marketplace and involve large areas, but state governments are showing interest in facilitating domestic markets.”

For more information on agroforestry and woodlots, read Agroforestry for Natural Resource Management, available from The Australian Agroforestry Foundation

For more information about The Food Forest in Gawler, South Australia, phone (08) 8522 6450