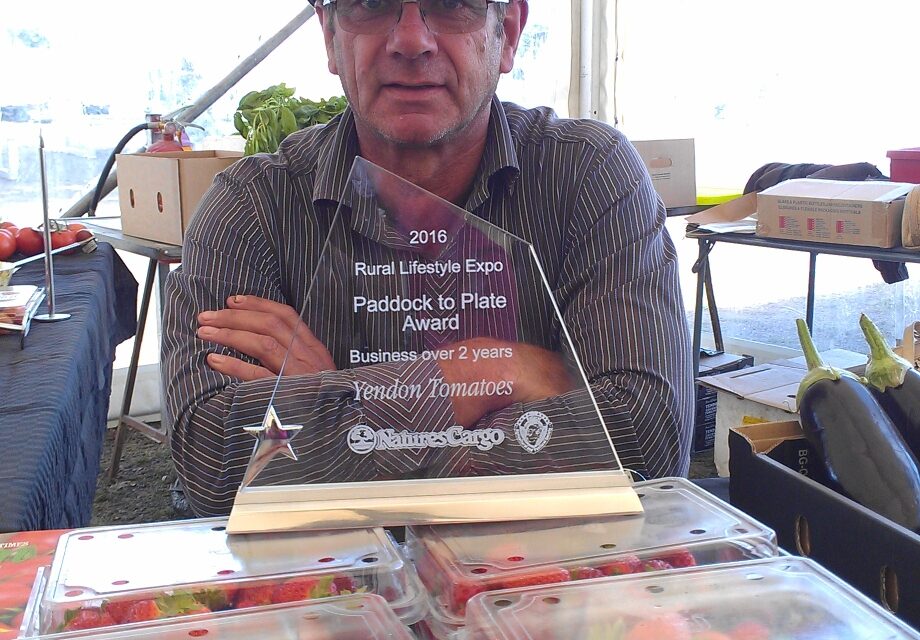

In an ever-growing industry that has seen many changes, John Elford is a survivor. He tells RICK BAYNE his story.

Some people reckon John Elford should be extinct.

As a small farm business operator growing hydroponic tomatoes at Yendon near Ballarat, John works with just a quarter-hectare of greenhouses on his 32ha farm.

“Twenty years ago, my farm would have been classed a medium size, but with better tech and the increase in corporate interest, the average size of greenhouses now would be about five hectares,” he said.

“Some say I should be extinct!”

While John admits the current climate is very tough, with small farmers being driven out through unnecessary regulation and increased running costs, he’s hanging in there.

John has been a member of the Hydroponic Farmers Federation (HFF) since 2001, even before he purchased his farm in 2002. He went on to join the committee in 2005 and became president in 2012 and still holds that position.

Without hydroponics and the HFF, John doubts he would still be in business.

“HFF is so valuable for sharing ideas, networking and keeping up-to-date with latest technology,” he said.

HFF is a state-based organisation with about 70 members and is affiliated with the national organisation Protected Cropping Australia.

The Australian Protected Cropping Industry is the fastest growing food producing sector in Australia with about six per cent annual growth, and an annual farm-gate value of $600 million, the equivalent of 20 per cent of the total flower and vegetable production.

Hydroponically-produced tomatoes account for more than 50 per cent of the Australian tomato market and 25 to 30 per cent of cucumber and capsicum production.

As a farmer, John is only a small part of the industry, but as president of the HFF, he has a big role in advancing the industry.

He’s happy to be a spokesman for hydroponics — growing plants not in soil but in water with added nutrients — and says that by significantly improving the growing environment, the system leads to faster growth, higher yields and better quality.

With hydroponic farming, you can also grow out of season, grow foreign plants in a local climate, control pests and avoid weeding or herbicides.

“There are major energy and water efficiencies and a much-reduced impact on the natural environment,” John said.

“I was attracted to growing something in a controlled way. Hydroponics gives certainty, you can predict what you’ll grow if managed correctly.

However, there are drawbacks.

“Selling through the wholesale market is very unpredictable and you are a price taker, depending on supply and demand to determine prices, and there are too many middle men,” John said.

“We only see about 50 per cent of the price you see in the supermarkets, which is why I target local restaurants and farmers’ markets.

“Focusing on making the business work puts a lot of pressure on relationships.”

John’s road to hydroponics started with some backyard plants during his 20-year career at Alcoa’s aluminium smelter at Portland before the family moved to Yendon, 20km south of Ballarat, in August 2002.

“I was the primary bread winner and our second child had just started secondary school. This meant my first wife Deborah at the time was looking for opportunities,” John said.

“We both came from dairy farming backgrounds and our children hadn’t had any exposure to farming, so we felt there was an opportunity to return to some sort of farming.”

They started researching options and a newspaper article sparked John’s interest in hydroponics. Their original plan was to purchase farmland in Portland and build a greenhouse, but while researching potential greenhouse structures, they came across an already constructed and once operational greenhouse in Yendon.

They decided to visit the farm not to purchase but to determine whether the structure would be suitable to construct in Portland.

The timing was opportune when they learnt that the owners had the property for sale.

“By the time we had returned to Portland, we had made the decision to discuss purchasing the already developed farm,” John said.

It would take another six months of negations to agree on terms and it was a big decision for the family to leave a secure job, uproot the children and leave a well-established group of friends.

But the big move paid off.

Today, Yendon Gourmet Tomatoes is a small operation focusing on quality, yield and efficiency and produces about 70,000kg of truss and cherry of tomatoes.

Tomato seedlings are planted at about five weeks old rather than using seeds, and coco peat is used as a growing medium, which is replaced every year.

Tomatoes like an environment kept at 15°C to 16°C overnight and 18°C to 20°C during the day and they receive a mix of 13 different nutrients fed as a dry powder.

Water is added as fertigation, but John has to carefully monitor the amounts.

“You shouldn’t feed or water a tomato too much or too little. Too much water and the leaves will go lighter coloured, whereas it’s better to have darker green foliage. Too little water and you don’t get the yields and they are more prone to disease.”

To diversify, John also grows basil, eggplant, cucumbers, capsicums and strawberries.

The industry is facing a big challenge with tomato brown rugos fruit virus.

“We have had lots of diseases over the years, but by far this is of most concern, not because of the disease but because of how our national and state government, in particular Agri Bio, are managing outbreaks,” John said.

“Without hesitation, farms are being shut down. The policy at the moment is eradication but our industry is pushing for management within the farms affected.

“International experience shows the virus has been managed for more than 10 years. It is of no danger to humans and only affects the way tomatoes look. However, growers are afraid of the whirlwind of government-sanctioned destruction that will be visited on them if the disease is detected on their farms.”

Despite the challenges, John says he is a lucky survivor who has developed a recognised brand and diversified into local farmers’ markets and restaurants.

Always happy to share his knowledge as well as his produce, John says customers still want to deal with a local grower.

Defying extinction