In the heart of Victoria’s historic apple country is a dairy farm that wants to grow up to be small — really, really small.

Among all the ‘ines’ of the animal kingdom, there’s this funny thing about canines and bovines.

When it comes to the dish-lickers, well — everyone knows you can’t teach an old dog new tricks.

And when it comes to older dairy cows, Tessa Sellar has learned the hard way they’re not so quick on the uptake either.

This one-woman show at the helm of Sellar Farmhouse Creamery quickly realised that was only the first step up a very steep learning curve as she set about creating a micro dairy at Harcourt in central Victoria.

Tessa Sellar has a herd of 10 but is keen to grow it to 12.

After interning full-time in the highly successful Holy Goat Cheese enterprise at Sutton Grange, Tessa moved on to her own business. She has been marketing her milk products for two years now, after an initial 18 months ironing out all the kinks in the establishment of her micro dairy.

Right now it is Tessa’s goal to build her milking herd to the dizzy heights of a metric dozen — as far as she is concerned, 10 milkers will be more than enough for the future of her dairying dreams.

“I have eight milkers right now, and some heifers coming through, which has taken me a little longer than I had planned — but even those initial setbacks were a valuable lesson for me,” Tessa explained.

“I won’t ever buy older cows again — I will breed my own and start them in the dairy as young females who will be able to grow with me as I continue refining my management practices to make the micro dairy deliver on all the things I have planned for it.”

And Tessa is not joking — she might be new to the dairy owner/operator club, but she is also proving a more-than-capable pioneer in her own right.

Because among other things, she is pretty confident she is the proud owner of Australia’s first, and only, licensed mobile milking parlour.

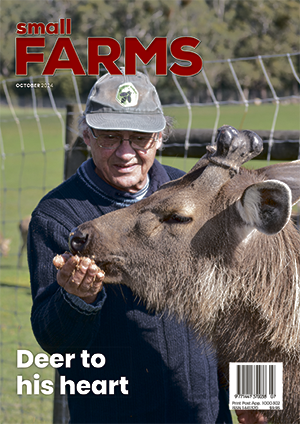

Tessa says the best part of dairying is hanging with the cows.

Photographer: Oliver Holmgren.

An innovation she describes as being — of all her equipment — the greatest success at the creamery, and a design she hopes will help the small-scale dairy movement become a big player in the wider market by making their owners more financially secure.

She says they will also have “many positive outcomes for cows and land” and she is delighted the concept has also been embraced by Dairy Food Safety Victoria.

“Whenever you have large numbers of animals regularly congregating in the same place, it’s pretty much a given you will end up with environmental problems,” Tessa explained.

“For example, the concentration of manure creates high levels of nitrogen, the plants which then grow are usually considered weeds, such as cape weed, mallow, nettles and others.

“Severe animal impact results in dusty bare ground in summer, burning off any fertility in the soil and making a hard-pack surface for water to run off.

“In winter it’s a muddy pit which leads to dirty animals — and as udders and teats get dirty the risk of mastitis increases, along with increased udder cleaning time.

“It’s also just not very pleasant, working in mud every day, cow and human alike.

“However, once you turn down the concentration dial, both these problems — fertility and impact — become incredibly valuable tools, if not vital, for restoring landscape functions. If only you could have these elements spread out across the paddock rather than concentrated in holding yards, laneways and dairy parlours.”

Enter Sellar Farmhouse Creamery’s mobile milking parlour — built by Tessa’s significant other Oli Holmgren, who has been responsible for conceiving, creating and commissioning the little farm’s infrastructure.

Tessa says the mobile milker is not a new concept. In Europe they are regularly used with smaller herds, particularly in grazing conditions such as the alpage (mountain pasture) where animals spend summers moving up the mountain to take advantage of magnificent pastures.

She says to bring the herd back down the mountain for milking daily would defeat the purpose completely.

“So we had many examples to offer inspiration when designing.

“While on my six-month sabbatical along the east coast, I spoke with many dairy farmers about this concept.

“It was at the dinner table at Elgaar Farm in Tasmania the basic design came together — after which Oli and I spent lots of time looking at the Ukranian mototecha model and, closer to home, Taranaki’s take on this at its Woodend home.

“From all that research Oli and I decided on the tweaks and alterations we would need to meet our needs.

“After all it seemed silly to do the washdown in the paddock, which would require hot and cold water and cleaning chemicals. We already have all these at the factory, so why not have all the equipment based on the back of a ute, which drives back to the factory with the milk.

“Many of the European models don’t have a floor but we decided for hygiene purposes we wanted a cleanable floor with good airflow, which means feet and milking equipment are always off the ground.

“At the same time we wanted the trailer as compact as possible for moving through gates and around paddocks.

“We did the calculations and — with the way we milk — discovered it wasn’t that much quicker to milk four than three. We then spun the stalls around, so they come in one side and out the other.

“It has room to evolve. Currently our vacuum pump can only milk one at a time. So I milk from the middle bay, with the cow on left on the cups while I prep the cow on the right and vice versa, just like a micro herringbone dairy.

“Then if we ever do expand to a bigger vacuum pump, I can milk from the back under the verandah, with cows in all three stalls.”

At Sellar Farmhouse Creamery, Tessa runs a calf-at-foot practice where calves spend their first three months nursing from their dam.

Tessa is something of a multitasker, as she is also running a calf-at-foot operation.

“So ideally I want all infrastructure in one. So at the back of the parlour is the pop-out calf pen with roof.

“After a week the calves spend the nights there, where they can still have contact with their mothers but can’t drink.”

But the cows can then come and go all night, checking on their calves and going out to graze. Then everyone’s nearby for milking in the morning (Tessa only milks once a day, getting about 70 litres) followed by letting the calves out for the day with their mothers.

“So much of milking is habitual for animals — but still, having a tame, calm herd is very important for training in a mobile milking system with no yards and laneways,” she said.

“So far it’s been successful. Within the first few days of training, all cows have been correctly in the parlour on cups.

“I say correctly, as often the first milking or two may involve them eating off the floor and having their back legs on the ground, reluctant to fully succumb to the stall.

“Some have been led in with a halter for the first few months.

“But when habit kicks in along with the hunger for breakfast, they all seem to walk themselves in, although this all takes time and patience.

“Once trained, they might be waiting for my arrival, or I can call a name and they come over from grazing but it’s a significant investment.”

Tessa said water was also a determining factor because of the way stationary dairies usually have a concrete holding yard where cows wait to come in.

She said this and the dairy must be cleaned out with water at the end of every milking, basically mixing excrement with water, significantly increasing the volume and “boy, do bacteria flourish in a moist environment”.

This ‘problematic’ waste is then held in settling ponds, making sure it doesn’t leak into any watercourses, and then spread back out over the paddocks with machinery.

Tessa said this was a huge water user; the average dairy milking 100 cows can use around 6000 litres a day in washdown (this includes the milking lines).

“The advantage of milking in the paddock is I just move the parlour before there is noticeable build-up of excrement and bare ground.”

If it does occur in the parlour, she simply sweeps it out and pours a bucket of water over until it’s clean.

“I only use 30 litres to wash down my milking lines each morning and the airflow over the mesh means it dries much quicker,” Tessa said.

“The second important factor in building a mobile milking parlour is we are leasing land.

“I need all my infrastructure to be portable so when I move properties, I can take all my investments with me.

“In all, the parlour cost us $12,000 in materials and 210 hours of Oli’s labour — although we have made a few adjustments over time, with many versions of power and vacuum pump location until we finally installed the inline milking lines.”

At Sellar Farmhouse Creamery, Tessa runs a calf-at-foot practice where calves spend their first three months nursing from their dam.

She says there are many pros and cons to this system and dairy farmers come to a place where their system works best for them and their herd.

Tessa says the modern dairy cow produces far more milk than required to raise her calf, so sharing it fairly isn’t detrimental to the calf. There are many factors to keep in mind when deciding how to raise your dairy calves — all the way from immediate removal through to cows nursing until they next calve.

“This is a very complicated debate. At its core, I don’t think many would argue calves allowed to nurse from their mothers mature as healthier, more resilient animals.

“So when breeding for future milkers, cows raised on their dam tend to be more resilient because, in many ways, a cow is little more than a rumen on legs thus healthy gut equals healthy cow.

“All I can talk to is the experience I’ve had, which is the first week after calving, cows are super hormone charged, then things settle down a bit. They are also highly vulnerable in those first couple of months and thus for me, the less stress I can put on the cow the better.

“My priority will always be the health of the cow — what she needs she gets.

“If her calf is far too violent and damaging her udder, then I need to restrict the time they spend together. The bond shared between cow and calf is a beauty to watch, even when reunited as adults it remains strong.”

Sellar Farmhouse Creamery holds a lease at the foothills of Leanganook, just outside of Harcourt, 9km from Castlemaine in central Victoria.

It sits 380m above sea level in rolling granite hills, with red gums and lightwoods dotting the landscape and an average rainfall around 560mm, mainly falling in the winter months.

Tessa’s herd is a long way from the mainstream dairy enterprise — and not just because it has just 10 cows.

She has selected Jerseys (which she describes as small-to-average sized, classic dairy cows with the highest butterfat content of the mainstream milking breeds in Australia) and the Dairy Shorthorn (both the quintessentially English Dairy Shorthorn and the Illawarra Dairy Shorthorn, an Australian breed which is a medium-size animal and far beefier than a modern dairy cow).

Sellar Farmhouse Creamery sells milk and yoghurt in one-litre glass bottles and jars.

Not just any glass either — it’s glass Tessa wants back, to refill during the next production cycle.

There are two ways to buy her products.

About 65 per cent is sold via the community supported agriculture (CSA) model where people pay three months upfront for a desired quantity of dairy products.

“They can then choose from one of the three pick-up locations: Monday, Fryerstown; Wednesday, Castlemaine Farmers’ Market; or Friday, from the farm shop,” Tessa said.

“We then sell the rest on a first-in, best-dressed basis at the farmers’ market.

“It would be so hard to succeed without the CSA program. The idea it to always be able to meet CSA orders and whatever is left goes to market.

“There is a $1 deposit on the bottles and when they do come back, they are washed and go through a commercial dishwasher at 80°C.

“The process for our products is pretty simple, and I certainly don’t like to take credit for it — that’s the work of our girls.

“We provide them food, they magically turn that into milk, I milk the cows, we transport it to our little factory, batch pasteurise at 63°C for 30 minutes, bottle it and send it out.”

And Tessa’s favourite thing about her business, as she saves for land of her own?

“The absolute best thing about dairying is I get to hang out with the cows.”

The herd is made up of Jerseys and Shorthorns.