Blimey. This is the tale of one small farming family that wasn’t going to take the lamentable state of the lime industry lying down. They set about creating a world first that has been the saviour of their enterprise and, at the same time, created one of the industry’s most closely-guarded secrets to success.

In Queensland it never pours but it floods. And when the floods are finished the rain comes back. And back. And back.

Just ask any producers north of Brisbane, say 160km north around Gympie, where so much rain has fallen since the floods started late last year (and kept going for months earlier this year) everything underfoot remains sodden.

So sodden the mere thought of getting the tractor out of the shed is nothing but a distant memory.

And while the flooding was devastating, the real heartbreak has been the subsequent rain, that just never stops and is now crippling many farmers, regardless of their production type.

Growing limes is tough enough, without post-harvest pressures added into the mix as they are vulnerable to “a million pests and diseases” but being harvested when green, not their mature yellow, means no fruit fly problems.

But they do get pests on the trees, they do get broad mite and, in years such as this, fungal problems — which can be treated without, instead spraying white oils and copper.

But when you are operating in a pretty small niche market, anything that throws a season (or more) out of whack is bound to hurt.

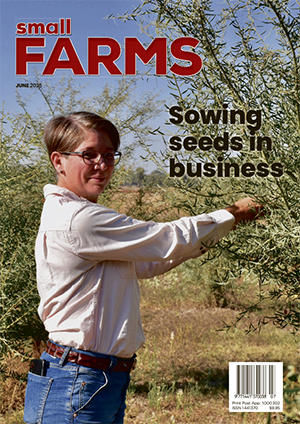

There was a time, according to Daniel Tabone, when 500 lime trees provided a pretty good living in his part of the sub-tropical north.

Then there was his own time, when 2000 trees (such as his) at Tandur (south-east of Gympie) were worth so little he would walk through the orchard with a big stick, belting branches so they would drop fruit and possibly help the tree re-flower to create a late season.

And the dropped fruit? That, Daniel says, was left exactly where it fell because it wasn’t even worth its cost of production, so certainly not worth the effort of picking up.

“I knew of another property, one year they were working with a packing shed and then sent their fruit away. But instead of a cheque, they received a bill – it had cost more to pack and freight their year’s work than it was worth,” Daniel said.

“It was a pretty grim time – the lime market is not huge at any time, and it doesn’t take much overproduction to smash prices at the consumer end of the business.”

“You can have your product in the market and suddenly another trucks arrives, with 50 trays and the spot price goes through the floor.”

By as early as 2007, Daniel said even Blind Freddie could read the writing on the wall with the lime industry.

He said so many people around him, and elsewhere, were planting row after row of lime trees — and something had to give.

For him, and his wife Linda, it was make the very quick shift to value adding and become a price maker instead of a price victim, or simply get out.

But having bought their little 28ha (70 acres) in God’s own country 20-odd years ago, the Tabones were not going to go down without a fight.

“It was a simple start, we took an old family lemon cordial recipe and swapped limes for lemon, and that seemed to do pretty well — but there were also plenty of others doing the same thing,” Daniel said.

“And we were still looking at how much we were throwing away and knew there had to be something else we could come up with.”

A mechanic by trade, Daniel put his thinking cap on and started to develop what may well have been the world’s first zesting machine.

Multiple improvements on and he has what he can only describe as a “benchtop monstrosity that’s got a mind of its own – and is a bugger to clean”.

But it works.

So let’s pause a moment and a quick lesson, in case you’ve suddenly got a little lost with this zesting business:

Definition of zest

1. A piece of the peel of a citrus fruit (such as an orange or lemon) used as flavouring.

2. An enjoyably exciting quality: piquancy adds zest to the performance.

3. Keen enjoyment: relish, gusto has a zest for living.

For the sake of further confusion, skip number three altogether and we’ll go with numbers one and two — and you can see the immediate implications for the lime industry.

That piece of peel — the zest — is a wafer thin slice, and if you have ever indulged in a bit of home zesting — such as grandma’s old cordial recipe — and done it by hand, you’ll see where this is now taking us.

Other lime growers have limes and cordial.

Yes, our heroes also have limes and cordials. They also have lime salt, dried limes, lime-based fizzy, lime based soft drink, sugar free products, lime juice and, obviously, zest.

Plus their trademarked Scurvy Dog; but more of that later.

The zest is the flavour-packed thin skin, skilfully extracted without any pith, which makes food and drinks bitter — whereas zest makes things, well, makes things zesty.

Daniel said it took 300 limes to produce roughly 1kg of zest – try doing that by hand and see how pleased you’d be if you never see another lime in your life.

However, the lime has an interesting, even history changing, story long before the Tabones turned to technology (and Scurvy Dog) to give their limes a new lease of life. At one point, limes were a jealously guarded military secret.

Most species and hybrids of citrus plants called ‘limes’ have varying origins within tropical Southeast Asia and South Asia. They were spread throughout the world via migration and trade. The makrut lime, in particular, was one of the earliest citrus fruits introduced to other parts of the world by humans.

They were spread into Micronesia and Polynesia – via the Austronesian expansion (roughly 3000-1500BCE). And later carried into the Middle East and Mediterranean region via the spice trade and incense trade routes from as early as 1200BCE.

To prevent scurvy during the 19th century, British sailors were issued a daily allowance of citrus, such as lemons, and later switched to limes.

The use of citrus was initially a closely guarded military secret, as scurvy was a common scourge of various national navies, and the ability to remain at sea for lengthy periods without contracting the disorder was a huge benefit for the military. British sailors thus acquired the nickname ‘Limey’ because of their use of limes.

Well if you think the military kept that a secret, you try and get even a glimpse of the Tabone Zestinator and see where it gets you.

We know it’s there; we’ve seen the results. We know the Tabones imagined, and then built it, because we have seen the mountains of zest produced by two people as opposed to an army of zesters (complete with missing fingers) slicing away to catch up.

But absolutely no way are you going to even hear what it’s made of, let alone see it. It’s behind a locked door and protected with security cameras. These dudes are deadly serious when it comes to their corporate security — and secrecy. While the competition flounders in the dark, the Tabones have added some zing to their zest capabilities and are going great guns in the price maker sector.

“We’ve lost count; but reckon this is about Mark VIII or IX and on a good day we can put through about 20kg of pure zest (if you remember our earlier maths, that’s about 6000 limes),” Daniel said.

The machine not only saved sliced fingers, it virtually saved the family business. Struggling under the load of intensive hands-on work, depressed markets, more lime trees still going in, gluts being dumped on the market at below cost-of-production prices and the occasional fire or flood.

Then there is the hand harvesting before entrusting 12 months of hard work into the hands of agents who will sell for whatever they can get.

The Tabones didn’t invent the Zestinator because they could, they did it because they had to. Not only did it save tonnes of quality fruit from being left to rot, it probably saved the business itself.

Born of necessity, the invention has saved their citrus farm at Tandur by preventing tonnes of perfectly good fruit from being dumped when gluts of fresh limes cause prices to plummet.

Initially they enlisted in the ranks of time-honoured hand zesters, creating a popular line of lime salts, dehydrated lime slices, cordials, and chilli lime sodas.

“At the time we thought if this keeps going we would take the plunge and invest in a machine — except we soon discovered there wasn’t one,” Daniel said.

Well there is now. It may not be set to the machined magnificence of a Swiss watch, but at 600kg it has an unquenchable appetite for limes.

Trays of the prized zest are then blast-frozen at -40℃ and soon after are winging their way around the country to distillers, restaurants and going into cocktails and is a hit with food and beverage manufacturers.

Daniel said as marvellous as the whole process sounds, and as cutting edge as the Zestinator appears, in the lime industry there was simply no way of escaping the hands-on responsibilities.

“Once we turn it on, there is no stopping until the whole run is finished,” he said.

“By no stopping I mean no smoko, no lunch (even toilet breaks are borderline) — we just don’t stop until it does.

“And as I said, it is a bit of a bugger to clean, as well, once you finish, so we only run it when we have to — but like I said, it makes it a lot more valuable than just juicing fruit.”

You can hear the pride in Daniel’s voice when he says the family business now has waste down to almost zero – and the business is going great guns compared to what he and Linda were facing 10 to15 years ago.

Today just five per cent of Suncoast Limes involves selling fresh limes — and then only the perfect ones. Everything else goes into the value-add column.

With frozen and liquid products the Tabones also have a 12-month business, not a seasonal panic, with everything riding on one or two cheques.

“Our value-added products are going out as much as we can make them, which is pretty good,” he said.

After more than a decade of exhausting years running the farm, value-adding and attending weekend markets, the couple has been able to step back from face-to-face sales and concentrate on production.

“We’re actually still getting people coming to us wanting our product, and most of our sales are now managed online — with a strong and loyal client base,” he said.

“We went hard for those first few years, but it has paid off.”

Note: Scurvy Dog. It’s as though it was always meant to be. Daniel said he had dreamt up the name years before they thought anything about value adding and was so taken with the name and logo he had it all trademarked. Scurvy Dog already looks set to be its biggest product yet.

“It’s a refreshing, spicy combination of Australian limes and chillies, with just the right level of bubbles. Enjoy it on its own or use it to make exciting and unique inspirations,” he said

“This is the real deal, no concentrates here, fresh green limes and lusty red chillies, grown in rich, local soil. The drink you can trust, with just a little bite.